In occupied Poland, the Germans introduced the same legal procedures as existed in the Third Reich. This included the German legal code, Nuremburg laws and military law. This was also to keep the German population in check as well as the occupied population. It provided simplified means for draconian punishments.

In September 1939, special German courts (Sondergericht) as well as military and field tribunals came into existence. The death sentence could be given. In September and October 1939, decisions relating to the death penalty were made by the Wehrmacht, the security police and the Gestapo. These three institutions together with local authorities managed also the prisons. In 1939 the Einsatzgruppen SS and Selbstschutz organised camps. They were termed internment camps (Internierungslager) although their function was more that of extermination. Poles were held there who had been captured as part of a plan to ‘politically clean the land’. Most inmates were murdered at places like Piaśnica, north of Gdynia or sent to concentration camps including Dachau. For example a huge group of Polish clerics were taken to Dachau.

Very few were freed and even fewer survived. These camps were converted into prison camps or concentration camps or were liquidated at the beginning of 1940 (e.g. Stutthof).

In order to simplify procedures, the prison service was managed by the police or the Justice Ministry. In the occupied territories, prisons came under the management of the SS and police (Höherer SS und Polizeiführer) through local SS and police (Kommandeur der Sicherheitspolizei und des Sicherheitsdienstes). This included such prisons as Pawiak in Warsaw, Montelupich in Kraków or Lublin castle. Many were also killed in these prisons.

In territories annexed to the Reich, prisons came under the local or district Gestapo. Each office had its own prison at its disposal. From 1941 there were also camps called Polizeigefängnis und Arbeitserziehungslager (police jail and labour education camp). There were also remand prisons which were often at the headquarters of the local Gestapo.

The Reich Justice Ministry also had its own prisons. Inmates were either on remand or serving their sentence. They were called Gerichtsgefängnisse (court prison). From 1942 prison camps called Stammlager were opened. They were located in such places as Fordon, Koronowo and Rawicz and prisoners were forced to do heavy labour in them.

Imprisonment in prison camps and labour education camps was also possible. Nazi employment law for Poles laid down the way in which labour could be exploited. The police, Gestapo and local administration chose those who were to be sent to work in Germany using terror and force.

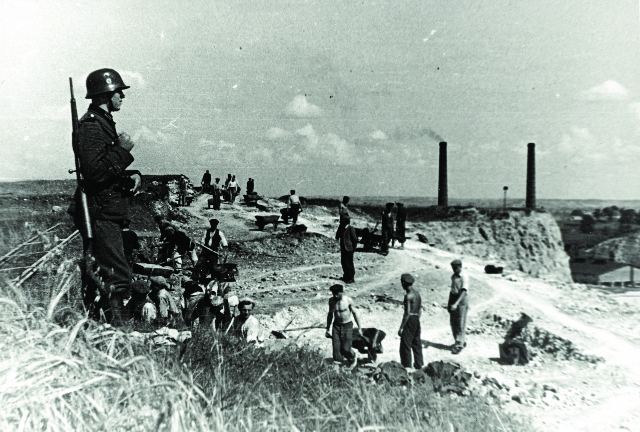

Poles had no right to legal protection whereas the interests of the Reich were safeguarded through a detailed system of repressing forced labourers. The German authorities decided upon the nature and location of work and people were sent to places according to the needs of the Third Reich. Therefore many people found themselves a long way from home. Workers were housed in work camps (Arbeitslager). Imprisonment could be the result of not working well enough or breaking some other minor law in the draconian system. In Poland there were around 1,750 labour camps and around 40 hard labour camps (Straflager, Arbeitsstraflager, Strafarbeitslager) and labour education camps (Arbeiterziehungslager‐AEL. Like everything else in the Nazi system, the word labour education camp was a euphemism for something much more sinister. The prisoner was unlikely to learn anything.

The labour education camps came about as the result of an order of Himmler of 28 May 1941. They were created in general in the territories annexed to the Reich and were based on prison camps. The camps were very hard and prisoners had to work for companies like IG Farbenindustrie, Siemens, Hermann Göring Werke and others. The local Sipo and SD were usually responsible for setting up such camps. The camp Kommandant and his deputy were Gestapo functionaries. The organisation of the camp required twelve hours heavy labour followed by pointless physical labour which was more akin to torture and physical exercises. In prison camps the workers were also tortured through violent interrogations accompanied by a regime of just bread and water, housing in complete darkness, forcing prisoners to do exhausting physical exercises and giving twenty or more strokes of the truncheon. Release was allowed once the sentence was served. If the Gestapo believed that imprisonment had not served its purpose, then the prisoner was sent to a concentration camp.

Apart from those AEL camps run by the Gestapo, from 1941 individual camps sprang up next to production companies, something that increased dramatically after the autumn of 1944. Inmates were almost entirely foreign forced labourers. In theory the Gestapo had to decide who would be sent to these camps, in practice it was the company. The company, alongside the local police, decided who would guard the camps. The laws for the AEL camps were not the same everywhere and had various names such as work education camp, education camp, special camp, Gestapo special camp, prison camp and police prison camp. In Upper Silesia there were special camps for Poles called Polenlager which were organised from 1942. Local people the Nazi authorities decided were dangerous to the interests of the Reich were imprisoned there. They were Poles known for their anti Nazi point of view or people who worked in Polish Silesian organisation or those who had refused to sign the ethnic German nationality lists (Volksliste). These camps were in old production halls and had no sanitary facilities. There was no limit on imprisonment in a Polenlager. Adults could work in Silesian industries or in agriculture. Up to around forty percent of the prisoners were children who had to work. The death rate was very high.

The term Polenlager was also used in Germany for camps employing Polish forced labourers. They were not the same as the camps of the same name in Upper Silesia.

Relations