One of the main political goals of the Third Reich was the incorporation of conquered territories into the economic system of Germany and to exploit them to the maximum possible. It was planned to employ the maximum number of Poles possible. Foreign workers were meant to replace Germans who had been called up the armed forces. Seasonal workers had come to Germany since the nineteenth century so there was nothing new in this – only the way in which it was used by the Nazi regime.

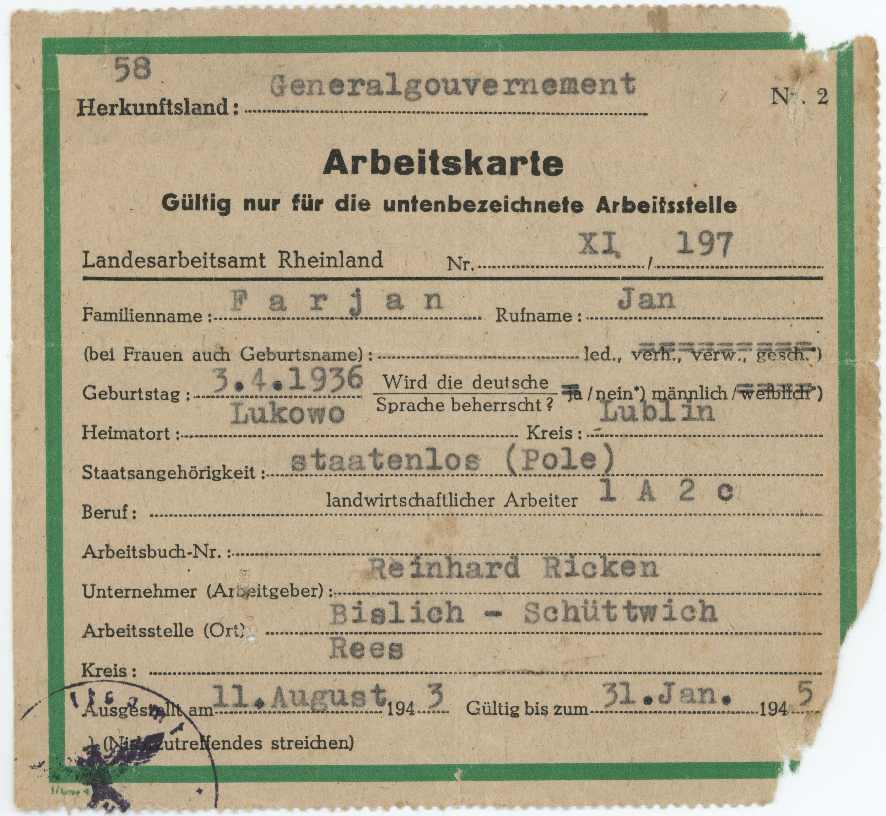

The tool for bringing this about was the employment offices, Arbeitsamt. The first one was set up within three days of the invasion of Poland and within one month there was a dense network of them throughout the occupied country.

Forced deportation of Poles to work in the Third Reich can be divided into several stages. The first stage started with the invasion and lasted until civil administration took over – that is September and October 1939.

Round ups followed as the German army occupied parts of Poland. This was for propaganda purposes back home as the state tried to convince Germans back home that there were advantages to the war. In the first two weeks of September 1939, some 13,000 people were sent to do agricultural work in East Prussia. They were employed alongside POWs in potato picking.

Once the employment offices were set up, things became more organised. They started to send people to the Reich in the second half of September 1939. The first transports went from Bydgoszcz, Gdynia, Gniezno and Upper Silesia. The employment offices had lists of people prepared by local Germans as those that should be sent to work or forced to leave the territory.

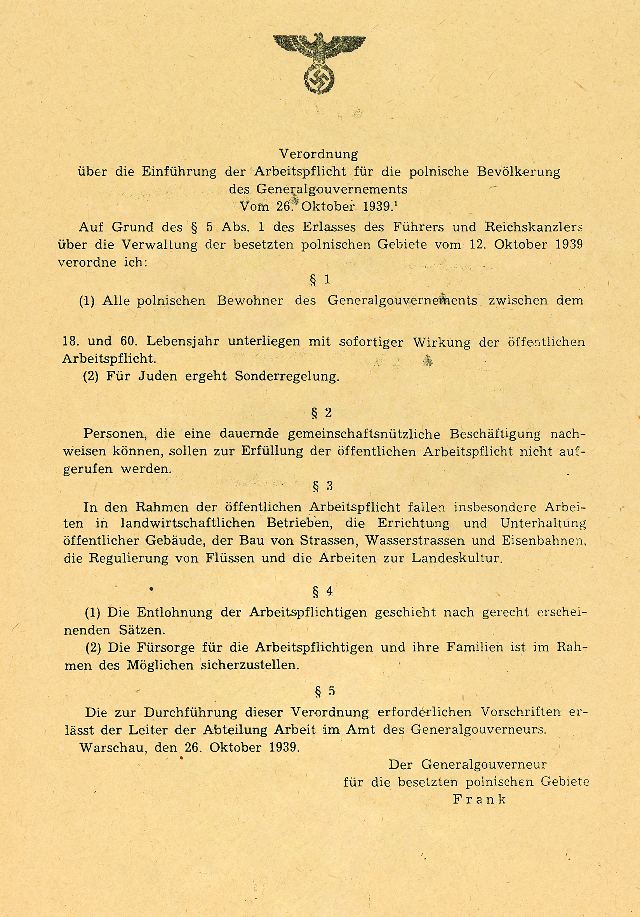

The second stage of the recruitment of forced labour occurred when the civil administration took over and lasted from 26 October 1939 until March 1942.

During this time POWs were employed. This was a policy dating to 1938 when it was decided that POW camps in the future should be set up near places which had a shortage of forced labour. Employment offices were required to keep a file on each POW and know what his profession was to ensure that he was properly employed.

The way labourers and especially intellectuals were recruited was different in the territories annexed to the Reich than in the General Government. In the annexed lands there was no voluntary recruitment. This was part of the Nazi ideology that Poles were a lower category of people and did not have the right to make decisions about their own fate and thus could be deported at any time, whether it was to the Government General or to the old Third Reich for forced labour. The employment offices prepared lists and those on these lists received a summons to appear before the Arbeitsamt. As far as the German authorities were concerned, they wanted to be rid of all Poles in this area in order to free it for German settlers.

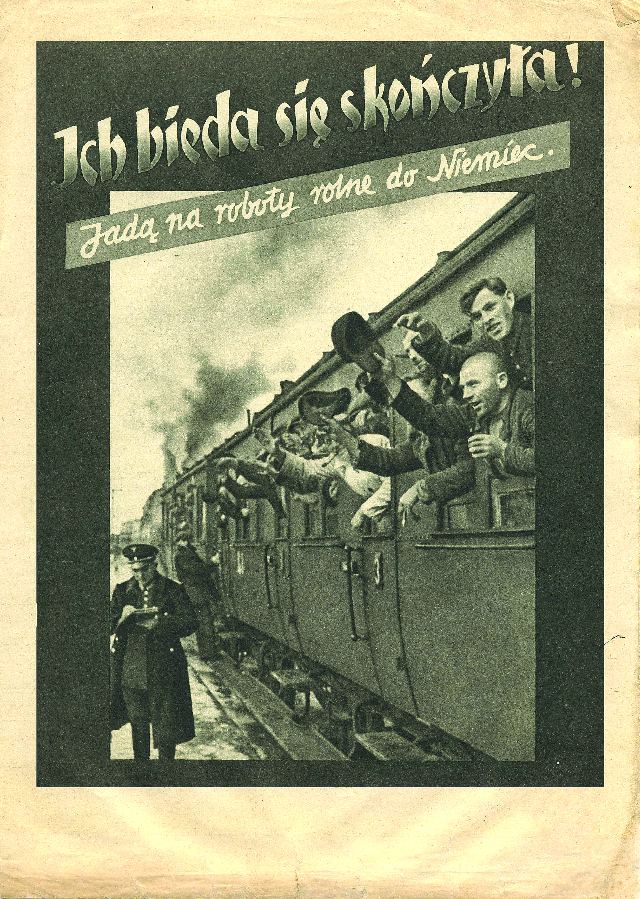

In the General Government there was a campaign to get people to volunteer to go to work in Germany.

The campaign was well funded but the results were less than expected.

By the beginning of 1940 it was clear that the General Government would not be a source of voluntary labour sufficient to meet Nazi requirements. In February 1940, various forms of force began to be used such as street round ups in cities and named lists in the countryside.

This was organised by the police and local authorities who were responsible for fulfilling a quota of workers. At the beginning, organisation was weak but in April 1940 when voluntary recruitment was dropped things changed. A common tactic was to hold one of the members of a family hostage in order to get another one to volunteer for work. The employment offices could punish, including corporal punishment, those it considered were not keeping its rules. The employment offices worked alongside local authorities, local Nazi party groups and the police.

Despite the terror, arrests, use of prison work camps and concentration camps, the effects were still not as planned. Instead of 500,000 people required, it was only possible to send to Germany 50,000 industrial workers and 160,000 agricultural workers.

Until 1941 the employment offices sent educated and young people to Germany believing that this would keep them out of resistance work at home.

Deportations slowed down in 1941 in view of the preparations for war with the USSR. Workers were needed in Poland, above all on transport systems, many of which had not been repaired following the September 1939 campaign and would be needed for carrying huge amounts of military equipment and troops to the east.

Once the war with the USSR began, locals were used to assist with the campaign in work such as carrying weapons and ammunition. It is hard to calculate how many people were involved in this although in those places where the front did not move so quickly this was the norm.

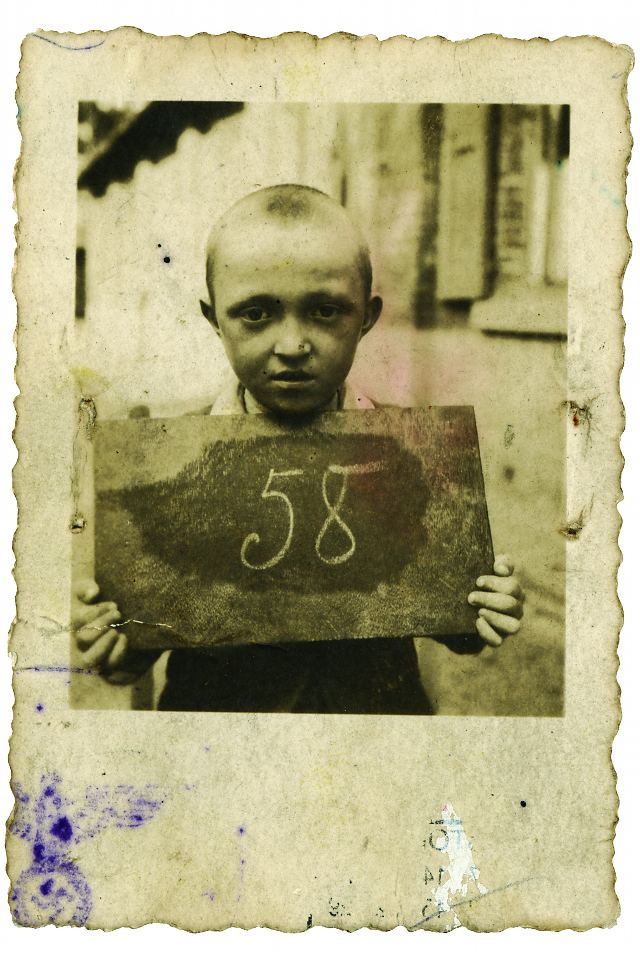

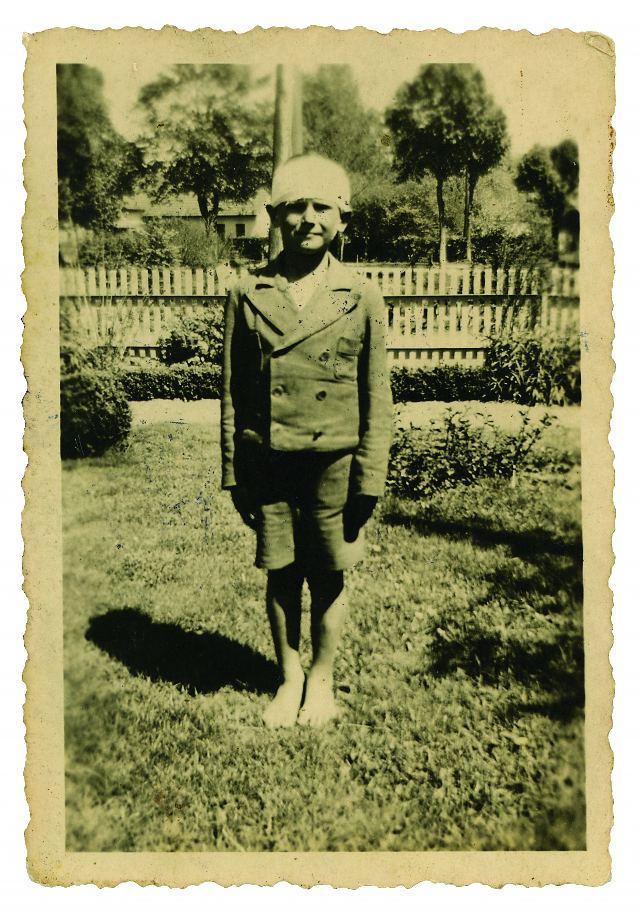

In 1941, there was a shortage of workers in the annexed territories. There were now two conflicting policies in place. The first was that Poles had to be deported to make way for Germans but in the second people were needed to work in industry. This labour shortage was most acute in areas that were industrialised such as Wielkopolska and Silesia, it was less so in the area around Ciechanów which was made up mainly of farmland and largely supplied agricultural workers for East Prussia. The result was that deportations were slowed down and that the authorities needed to employ increasingly younger children.

The next stage in the deportation process was linked to the office of the General Plenipotentiary for Labour Deployment which was in existence from March 1942 until February 1943. This office was a decision of Hitler and became an independent organ of the state administration. It had a great deal of power to recruit workers in the occupied countries through its local offices which from April 1942 were controlled by the local Gauleiter. This was designed to centralise the acquisition of labour and make the Nazi regional leaders responsible for it. On 7 May 1942, Fritz Sauckel who was in charge of the programme, ordered that where there were no volunteers, then force had to be used. Secretly he also agreed that laws protecting Polish children could be ignored. This led to even more younger children being forced to work for the Nazis and women also being forcibly recruited. At Nuremburg, Sauckel admitted that fewer than 200,000 people had come to Germany voluntarily. He was hanged in October 1946.

The fourth stage began after the German defeat at Stalingrad and continued until the end of the war. During this stage there were no rules whatsoever regarding how workers were found. There was total mobilisation at any price, no matter how cruel. As younger Germans were needed at the front, then their place at home was taken by increasingly younger forced labourers. The Nazi authorities did not even try to pretend to be obeying any rules. Labourers were kidnapped through round ups, pacifications and mass deportations. Tens of thousands of people from the Zamość area were sent to Germany in 1943. In March 1943, 23,500 people were sent from the Wartheland to farms in occupied France managed by the Germans. Efficiency became the key. It was now commonplace to employ women, children under twelve and concentration camp prisoners. From the beginning of 1943, the Nazis understood that the high death rate was working against the interests of the Third Reich. Families were then allowed to send food parcels which improved the lot of starving prisoners to a small extent.

The last wave of forced labourers were those that were forcibly evacuated as the eastern front approached. In some cases this ended with the victims being killed alongside their ‘masters’ when liberation seemed to be near.

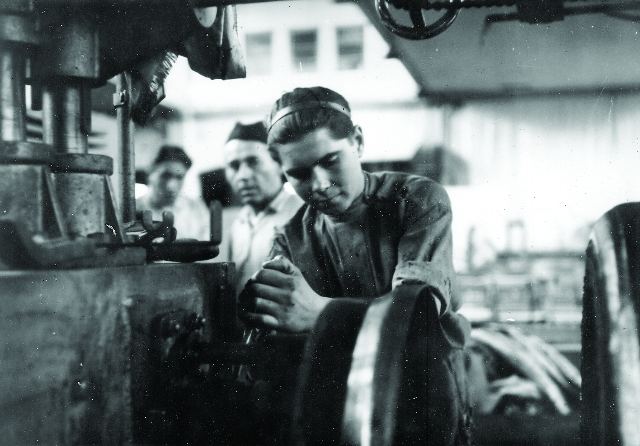

Life was very difficult for Poles who were taken for forced labour. German laws discriminated against Poles and citizens of the USSR. Their lot was worse than those people from other countries. There were no contracts and they were sent directly to those employers who declared that they needed labour. Poles had no right to choose places of employment. The hours were set by the employer. Agricultural workers started early in the morning and worked until it was night, irrespective of Sundays and public holidays. From 1942 holidays were no longer permitted. The German employers paid no social or health security. Pregnant women had to work the same and only got a few days off for maternity leave. Young people had to work in the same conditions as adults but they received less pay. Most Poles went hungry. It was rare for them to receive more than 1,500 calories. They were unable to buy anything which was rationed in Germany. They had to wear a large letter P on their clothing. They could not leave the place they lived without special permission. They could not be in public places, attend cultural events, travel by train without a permit, get married, go to church. They were also completely forbidden to have intimate relations with Germans.

Poles who worked in agriculture often had to live in barns and outhouses, sometimes with animals. Those that worked in industry had to live in camps with various other people. Sometimes these camps were not suited as living quarters being in barracks, dance halls, factories or anywhere else that the employers could find.

The hard living conditions had a bad effect on the health of the workers. Many got sick and had no access to medical assistance. Seriously ill people were sent home. Workers fell under Gestapo jurisdiction and even for minor infractions or false accusations could find themselves in a concentration camp. The German employers could also punish Poles, including with physical punishment.

In theory Poles could only be employed in the Old Reich‐that is in the borders of 1937‐although in practice they were sent anywhere. They could find themselves in the Arctic Circle, Italy or the Channel Islands on fortification work. Around 50,000 Poles were in the Sudetenland, 113,000 in Austria and the annexed parts of Slovenia, thousands were in Alsace, Lorraine, Luxembourg and Belgium, 23,000 in occupied France. Poles were employed in railway yards across Nazi occupied Europe.

It is hard to establish exactly how many people were deported for forced labour. Sources vary from 1,700,000 according to Ulrich Herbert to 3,200,000 according to victims’ organisations. Czesław Łuczak, an economic historian of the Third Reich gives a total of 2,857,500 people.

Relations