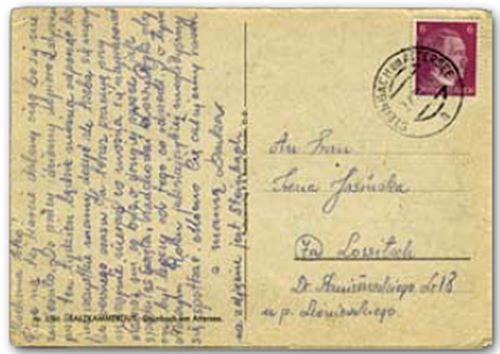

for the entire duration of the war, correspondence of forced laborers deported to Germany, was subject to inspection. Until 1940, random checks were carried out by the Gestapo. In 1941, in each administrative district the Auslandsbriefprüfstelle – “control offices of foreign correspondence” were created and cooperated in this action with the police. It was meant especially to prevent that information on the army, objects under special protection and news on the morale of the people in the Reich would become known outside its territory. It was also forbidden to write about the conditions of forced labor. In practice, this rule was not enforced (that is why the Reich’s campaign which was meant to recruit people in the Eastern Territories did not work and the number of people volunteering to settle in annexed territories greatly reduced). The tone in many of the letters was quite liberal and in many of them there were quite a lot of sharp comments on the German employers. Freedom of correspondence was greater in the case of accommodation outside the camps or in workers’ housing. In these camps it was allowed to send only one letter per month. Special two-part postcards were issued, designed to produce simultaneously a response of the recipient’s card, which resembled a correspondence procedure used in POW camps and concentration camps. On the pages of this type of card a very limited number of words could be written. Poles were also forbidden to send postcards everywhere – although in practise this rule was not always followed. An additional measure was the destruction by German authorities of letters and postcards written vaguely or illegibly. As a result of this measure, many of the recipients did not receive any letters. Many of the deportees, who had just completed several classes of elementary school and did not use writing every day, did not have a very discerning handwriting. This meant a loss of contact with their loved ones. That was also the case with children.

An interesting telegram is presented here. It was sent from the Ostrów Wielkopolski district (Kr. Ostrowo) to a forced laborer employed on the estate in Bonfeld, Heidenheim district. It informed the laborer about the death of her father, and the date of funeral (Thursday, 8 pm – 8 Nachmittags Donerstag). The sender was her mother. At the bottom appeared the words: Amt der Beglaubigte Komisar Görsch – Authenticated by the Commissioner of the Office Görsch. If a forced laborer would receive a telegraphic notice regarding the death of a close person, it could be a basis for granting leave. The telegram, however, had to be adressed to the residence of the recipient and had to be approved by the Gestapo police authority (in this situation, Commissioner Göscha). There were no fixed regulations how the police and the Gestapo were supposed to evaluate the telegram, other than to perform political assessment on the deceased and his family. In the case of an unfavorable evaluation, such approval was not issued. Likewise, if the person’s death was the result of German repression of the Wehrmacht, etc. Even with a positive opinion of the police, the on-site Labor Office could withhold leave – as a result, leaves of this type were rarely granted.